Overfed & Undernourished Pt 2/2

“Food as a Weapon, a two part series”

To read the first release, go here.

The idea of the weaponization of food seems almost paradoxical at first.

How can something meant to sustain human life simultaneously act as a system of defense or destruction?

By definition, food alone is not a weapon. However, when people, more specifically large institutions or governments, move to own the means of production, distribution and ultimately costs of our food, our sustenance transforms into the ultimate lever for control.

As America’s presence on the world stage grew through the first two world wars, intelligent people in charge of protecting America’s interests designed an incredible system of reliance in the 1970s: export dollars and export food.

Who can blame the United States for wanting to protect its interests? After all, our culture reflected a growing contempt for war and human suffering, coming out of World War II into Vietnam and the Cold War, and at the same time threats abroad seemingly grew overnight. Protecting Western ideologies and lives had become remarkably complex and obviously remained an acute concern for leaders in the United States as America looked to fend off the Communist uprising happening in Europe and South America. Exporting dollars and food allowed American authorities to harness control over friend and foe to serve the interests of Uncle Sam as he pleased. If America could find a way to leverage war through non-violent methods, it may work as a way to move the real wars from the battlefields to the banks and barnyards. But at what cost?

History hardly ever fairly represents the reality of trade-offs in decision-making, especially when the consequences take years or decades to play themselves out. Since the advent of the weaponization of food in the 1970s, it has become clear that the costs have been immense. Food production became institutionalized, concentrated, and commercialized at the same time food became less healthy, more processed, and less local. In other words, food production has become less healthy for all stakeholders from the individual consumer to the planet.

Don’t believe me? Look no further than the rise of obesity and chronic diseases in people across America and the rise in demand for advanced medicine to treat these illnesses inherited from poor nutrition. The birth of “Big Pharma” can almost entirely be linked to American food policy. Odd to say the least. Not to mention the growing environmental concerns draped around the global food production industry. The production model adopts environmentally harmful practices in order to navigate towards the end goal of producing as much food as possible. In the process, industrialized farming has become entirely reliant on fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and other harmful inputs, only to create unhealthy, nutrient-deprived food. The corn, wheat, and soy production in the United States reflect the poorly aligned incentives propagated by food insurance. Farmers in the United States were paid to produce crops that did not benefit profits, people, or planet. The harm in eliminating survival from food production incentives starting in 1938, over the course of decades, has single-handedly enabled harmful monoculture practices to flourish and our underlying health to decline.

So what good did we get out of these policies? American food policy, predicated on controlling geopolitical events via global trade, has reared its ugly head. Most people reading this article have no problem finding examples of the spiraling health crisis in the United States, and like me, are disturbed by the current state. Understanding the perceived positives, or at least the justification, for promoting these food policies centered around the production model in the United States retains immense value.

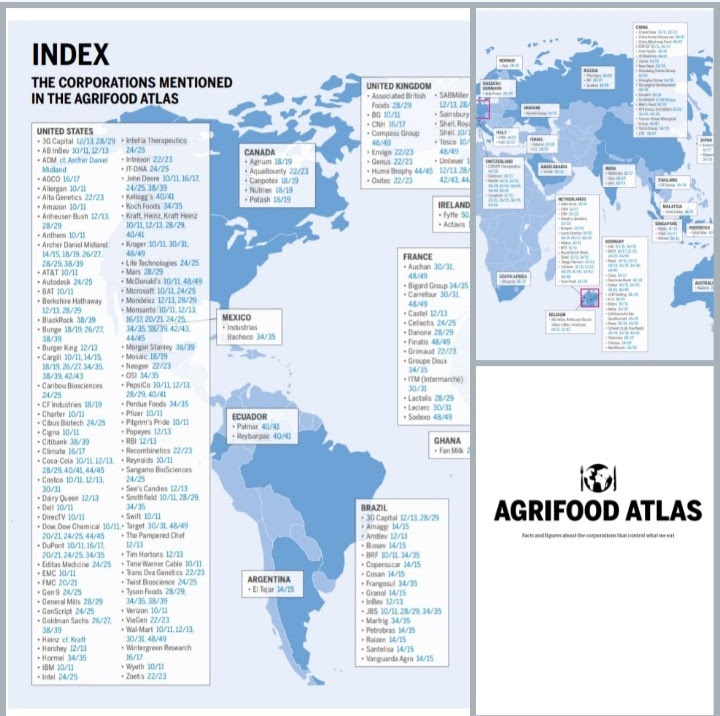

Control is the key. If America produced enough food to support the world food system, America retained its sphere of influence. If America emphasized large farms and large production output, it meant less than 5% of the labor force needed to support the food system. The rest of the human capital could flow into jobs focused on engineering new technologies, financial services, consulting, or other jobs in these growing areas of the economy. Pushing more human capital from the fields to the factories allowed for human capital to flourish in the production of new goods and services to benefit society and create more jobs for people to participate in the global economy. If the world population was fed, regional stability stood a chance of being controlled. Many parts of the world still face threats of famine regularly, however, the United States and United Nations have a depth of resources to provide aid. As mentioned previously, the control gained through exporting massive amounts of food globally gave America the perceived upper hand in geopolitics with Russia and other friends and foes during the Cold War and beyond. The consequences of losing that battle, however terrible the long-term negative effects of a broken food system may be, may actually have been the most defensive short-term decision that needed to be made at the time.

The evolution of food production in the United States from the beginning of the twentieth century until today tells a story of centralization attributed to poorly derived incentives pushed from the top down. The incentives ultimately worked to sidestep the natural governors supporting decision making and the consequences directly and indirectly affected all long-term stakeholders.

Who are the stakeholders and how have they been affected? The list of stakeholders when it comes to food production is endless. No, seriously. Food production affects all of us in more ways than one, most obviously through providing nutrients to support our lives and less obviously through the mark that farming practices leave on our planet’s health. The production model, which demands farmers to focus on the total output of the farm, is particularly harmful from an environmental perspective. Since it promotes the mass production of monoculture, the method also promotes the mass extraction of valuable nutrients from the soil. If those nutrients never re-enter the soil, the farmers then face the problem of becoming reliant on fertilizers and other agrochemicals to grow their crops. The availability of healthy soil has been depleting for years due to these monoculture practices and civilizations from the Roman Empire to the Jamestown settlements have collapsed because the food supply could not keep up with the population growth at the same time the soil was degrading from monoculture.

Whom do we have to thank for leading us to the current state of the food system? The cast of characters, technological advancements, and events fueling the production model's growth seemingly have a long list of culprits.

Enter Earl Butz.

Earl Butz: From rural Indiana to Pioneering Policy Maker

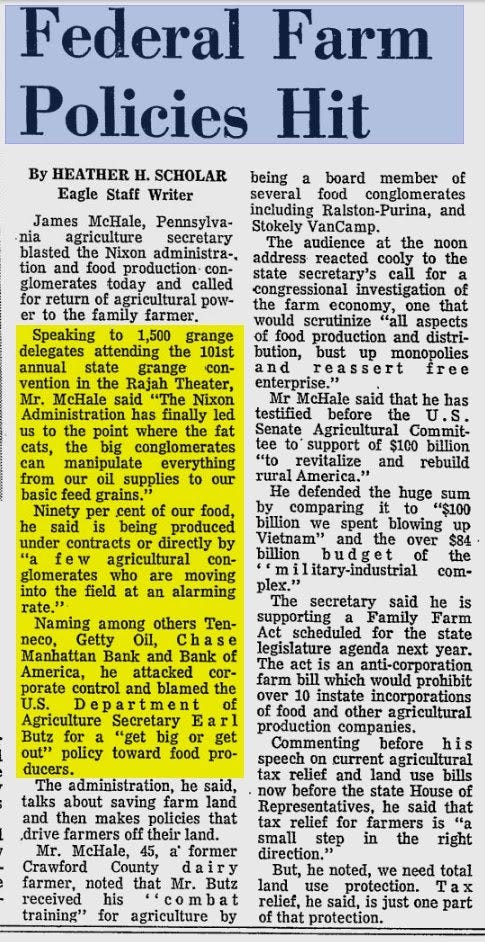

In many ways, Earl Butz embodies the essence of the production model of agriculture. In interviews, he spoke with boldness and purpose. A visionary thinker with a cut-throat, blue-collar mentality towards life, Butz hardly ever minced words. Butz famously coined the expressions, “adapt or die, resist and perish” and “get big or get out” in reference to farming production across the United States. The message was mostly directed at small farmers and ultimately led to many small farms going out of business. Most notably, Butz also made the comment mentioned at the beginning of the article: “food is a weapon”. His ideology around food’s role in global trade had a monumental influence over the shape of the farming industry in the United States.

So who is Earl Butz? As a child raised in northeastern Indiana, Earl Butz developed a grit towards life by working on his parent’s 160-acre farm. Ironically, the style of the farm his family operated sounded like a true regenerative farm, consisting of cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, and a small garden. He left small-town Indiana for greener pastures, attending Purdue University and later becoming the esteemed Secretary of Agriculture under President Richard Nixon.

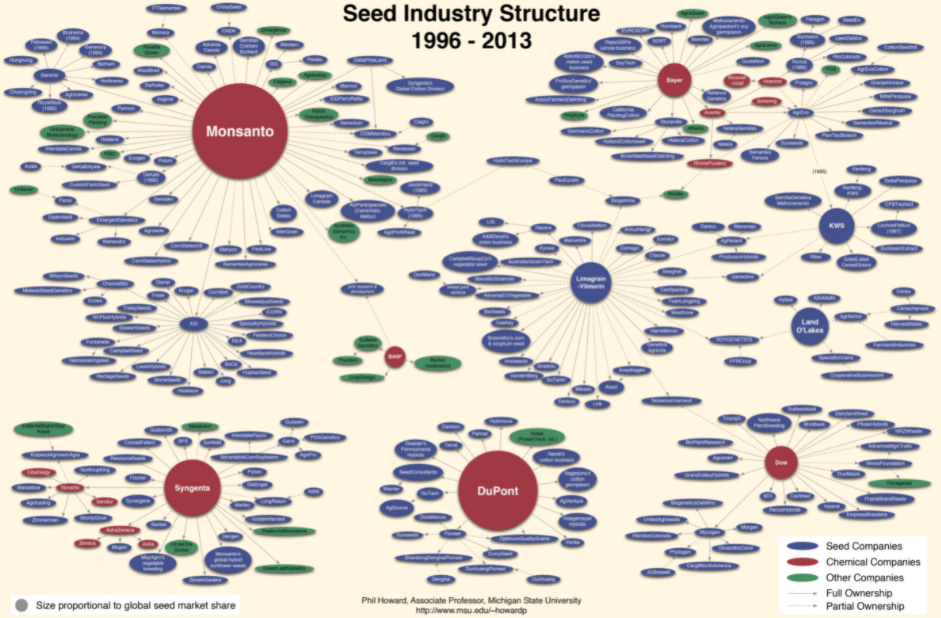

Whether correct or not, Earl stood behind the philosophy of the production model during his tenure as Secretary of Agriculture. The production model hung its hat on a narrow vision: feed the world through highly engineered ways of farming. Butz claimed he never intended to kill the small farmers in the United States, but he did in many ways. The incentives put in place to produce more and more corn and wheat outstripped the small farmers' ability to maintain a profitable enterprise. The only farming businesses able to survive produced the most easily sellable goods at massive scale. In other words, the farms grew acres and acres of corn and wheat via methods induced by chemicals across each stage. Farming had become so production focus and reliance on agrochemicals that any income statement of a farmer illustrated the power agrochemical businesses held over the farmers. My previous article highlights the monopolistic control within the agrochemical industry, but I left out a key detail. Mr. Butz, the sitting Secretary of Agriculture, stood to benefit immensely from the growth of these select agrochemical companies due to his ownership position in them. Yet another example of misalignment of incentives eroding the quality of the food production process. Since the entire industry focused on highly engineered production, any changes in the costs of these inputs had remarkably sensitivity on the bottom line of the farms.

Earl Butz’s vision fueled the production model of agriculture in the United States and around the globe. He understood the deep connections between global economics, foreign policy, and food production. As long as the United States dominated food production globally, the nation’s interests abroad remained protected by the abundance of food it managed to produce each year. The vision of feeding the world appeared noble on the surface, particularly when considering it meant the United States farmers may stand to see the ultimate benefits of producing the food to accomplish the goal. However, as it turns out, the layers to the story demand a closer examination of the environmental, ecological, and economic implications of the production model, all of which have fed into the erosion of Americans' health.

Take a peak - share your thoughts.

Leaders in Agricultural Policy A Conversation with Earl Butz (02/1993)

Written by: @clemenza