The Pursuit of New and Productive Soil

An excerpt by George Washington describes the struggles many of the early colonists faced in finding ways to sustain life through food production and generating sustainable economic value through the production of Tobacco and other cash crops.

"A few years more of increased sterility will drive the Inhabitants of the Atlantic States westward for support; whereas if they were taught how to improve the old, instead of going in pursuit of new and productive soil, they would make these acres which now scarcely yield them anything, turn out beneficial to themselves."

George Washington

From Europe to America. From Land to Lab.

The food system has been on the run for years in search of higher levels of production. As mentioned in last week’s article, however, focusing solely on the production of food without addressing some of the negative externalities of the production process itself has led to the downfall of many major civilizations throughout history. At the current juncture, the food production system rests on top of the underlying agenda to move from the land to the lab. Migrating from the pastures to a more controlled setting allows the input variables and output factors in the process to fall under a more precisely designed and managed process. But, as we see the rise of lab-grown food products such as Beyond Meat become more normalized, it begs the question of whether other options exist to more adequately address the three core food production questions:

- Can we produce enough food to sustain the expected population growth?

- Can we produce enough food to sustain the expected population growth in an environmentally conscious way?

- Can we produce enough food to sustain the expected population growth in a way that supports the highest level of sustenance of the end consumer at the most reasonable prices?

The Land Solution and the Lab Solution

The three core questions mentioned above demand more consideration from a broader contingency of people – or in other words it is time to find your food intelligence.

Specifically, ask yourself in what order do these questions need to be addressed?

As a thought experiment, take lab-grown food - if you even dare to call it food. If lab-grown food can help feed the world, does it satisfy the nutritional requirements for a higher percentage of people to flourish relative to other forms of food production? Take regenerative agriculture, for instance - can it restore the planet and provide the highest nutritional factor of food for people, while operating on a scale large enough to feed the world? These thought experiments dilute the questions into three interconnected concepts – the collective humanity, the environment, and the individual. The next part of the question is to ask what are some possible ways to most adequately address these different participants in the food system?

For instance, prioritizing humanity is most certainly the end goal, but can we accomplish that without addressing environmental complications in the food system? History would tell you, based on thousands of years of societal collapses, that the answer is no. At the same token, can optimizing for an individual’s optimal nutrition occur in a world with a depleted environment. Again, history would tell you no.

Prioritizing the environment provides the luxury to continue to grow concerned about addressing the other two problems - the individual and humanity. Said differently, we no longer can ponder the question of nutritional optimization or whether humans can produce enough food if we continue to deplete the environment at the current rate. To quantify the current mounting environmental crisis, the estimated rate of world soil erosion across the globe is occurring 20 times faster than the natural geological rate. None of these dilemmas offer a simple singular answer, however, if modern society wants to avoid the ecological woes of failed civilizations of the past, addressing the environmental concerns remains as true now as it did when George Washington saw the destructive practices in the early Americas used. Migrating some of the food systems to labs may work to temporarily solve part of the problem but avoiding restoring fertility to the land altogether poses a quiet risk with substantial societal implications.

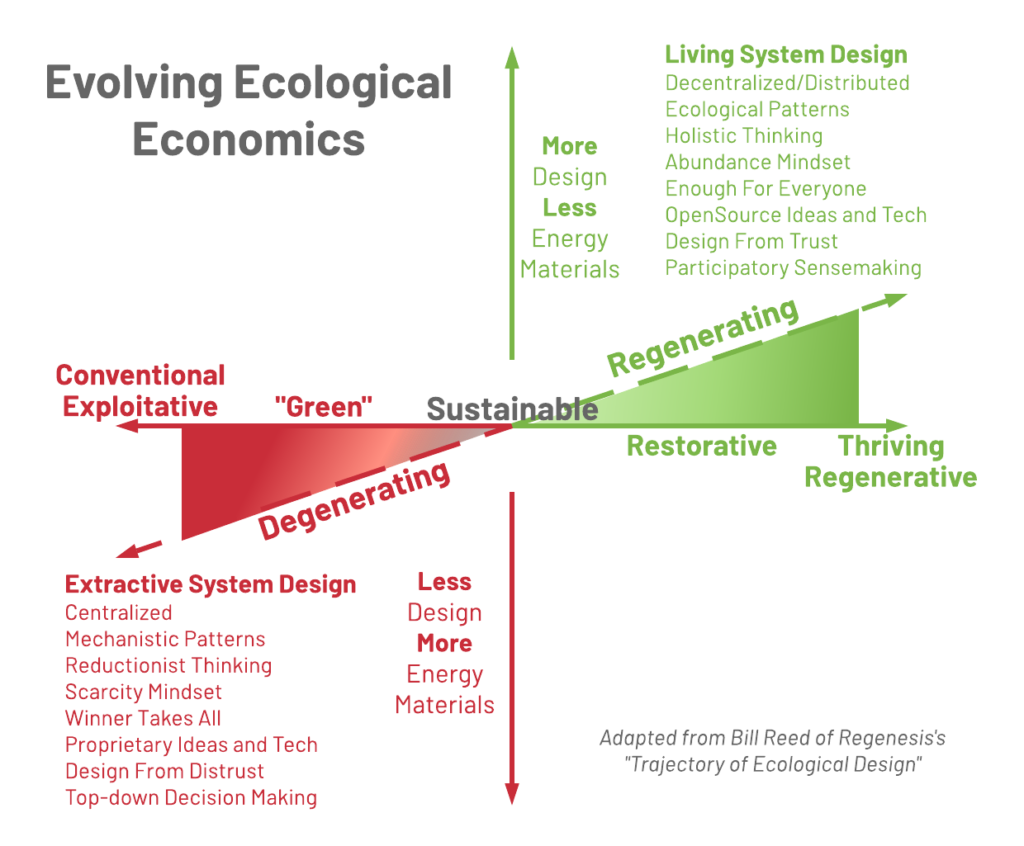

For these reasons and many others, it has become apparent to many farmers and food system professionals that Regenerative Agriculture practices demand more attention from all participants from policymakers to your vegan environmentalist friend up the street. The basis of the Regenerative Agriculture movement operates from a first principals’ mindset in more ways than one – more clearly stated preserving the environment is the first order of business in regard to creating a sustainable food system for the future, healthy individuals, and thriving humanity. But what exactly does that look like? What practices need to be implemented in order to shift our focus to a more sustainable, localized, and prosperous future?

Basic Principals of Regenerative Agriculture

The principals of the Regenerative Agriculture movement are centered around Gabe Brown’s 5 Principals of Soil Health:

- Limit Disturbance

- Armor the Soil Surface

- Build Diversity

- Keep Living Roots in the Soil

- Integrate Animals

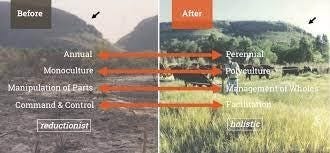

These practices typically require no-till farming to limit soil disruption, diverse cover crops, crop rotations, on-farm fertility, minimized use of herbicides, and avoiding all pesticides, insecticides, and synthetic fertilizers. Lastly, it involves integrating livestock back onto the land too. At its core, the Regenerative Agriculture movement stands to restore the land by creating environments that mimic nature as opposed to pumping the soil full of chemicals to increase crop production.

Taking it one step further, Regenerative Agriculture aims to restore the natural evolutionary functions that the production model has taught people to destruct. Specifically, these regenerative methods promote better carbon cycling, energy, water, and microbial cycling as well as better overall community dynamics.

Carbon Cycle: Refueling the Soil and Purifying the Air

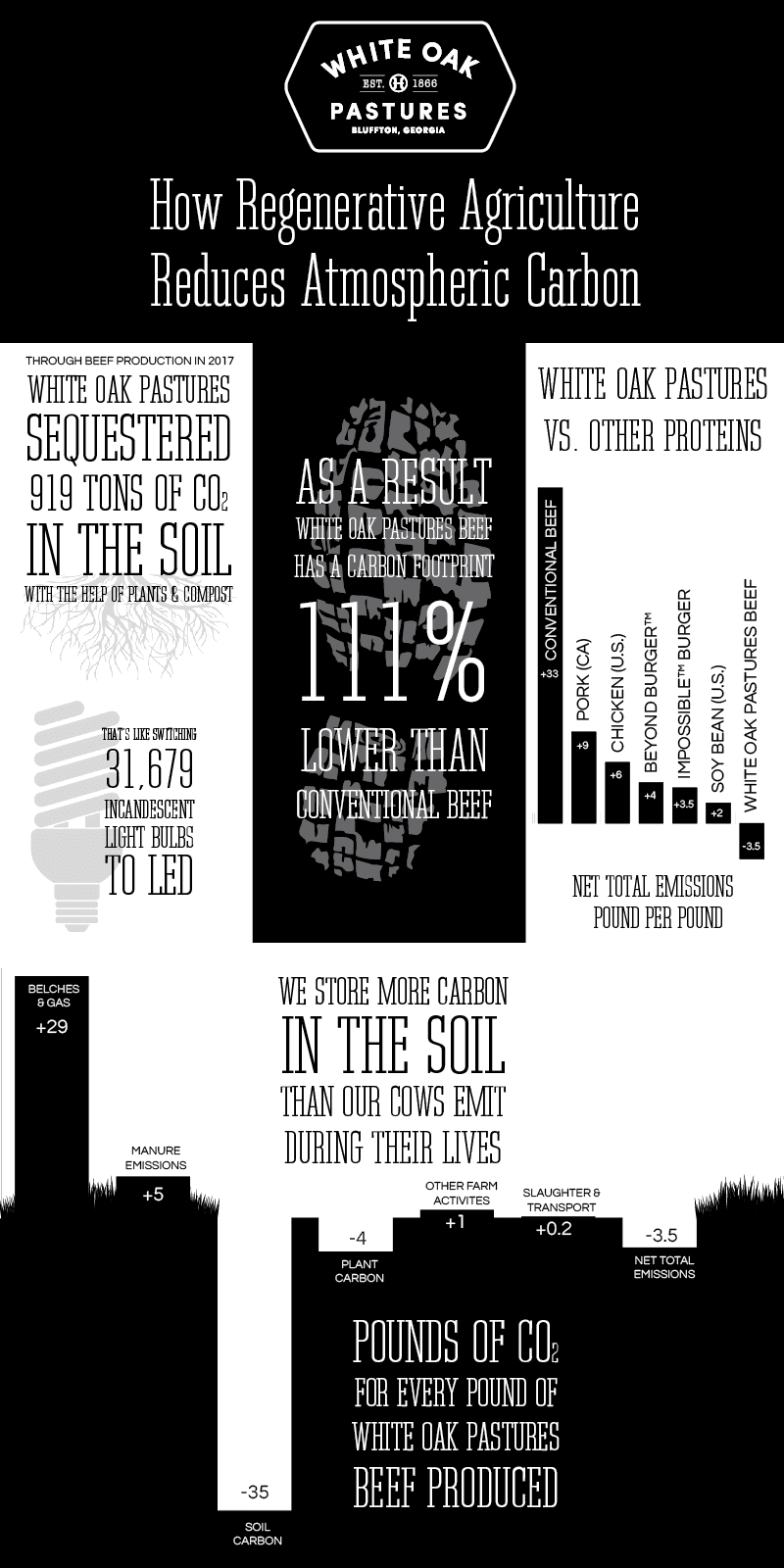

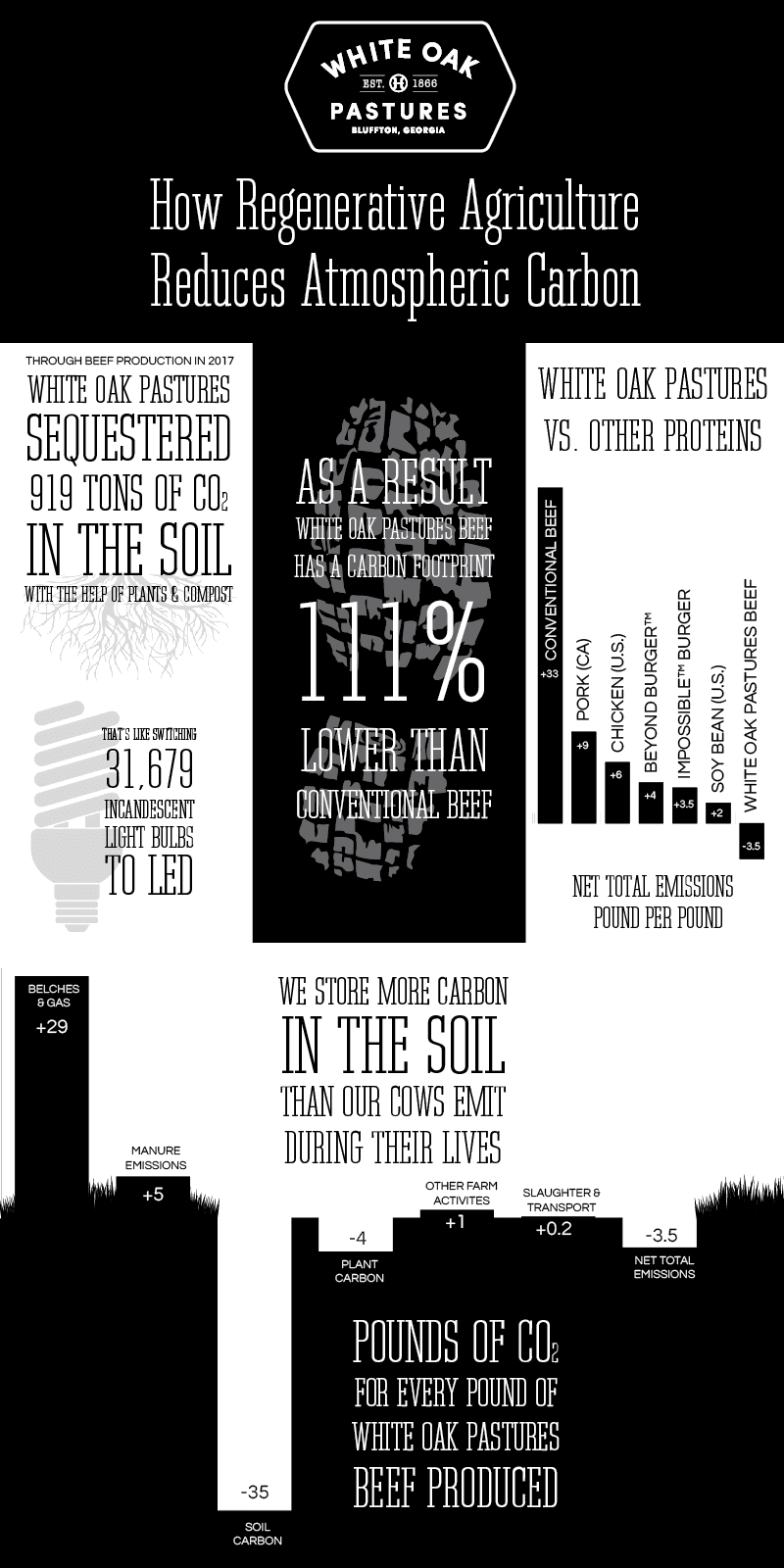

Greenhouse gas pollution has long been discussed by environmentalists as a major concern as it relates to climate change. Carbon emissions is a hot-button topic, however, less discussed in the mainstream narrative is the potential to use the soil to sequester carbon from the atmosphere. Currently, agriculture accounts for roughly 15% of greenhouse gas emissions, however, studies show that agriculture can act as a 15 to 20% greenhouse gas offset or negative contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

Carbon in the soil, in large part due to conventional farming practices, has been drained. Will Harris, who runs White Oak Pastures in Georgia, discusses the difference between organic matter on his farm and his neighbor’s farm on his amazing blog post the Cycles of Nature.

The picture above shows the difference between essentially dead, infertile soil and the White Oak Pastures soil. The sample is taken from land 50 feet apart from each other and it shows the true essence of regenerative practices – protecting the soil and restoring the soil can lead to better outcomes for the planet and people.

A key component of restoring the carbon into the soil involves mimicking nature in a way that it recognizes, which includes adding animals to the fields to help with nutrient cycling. However, if you have been paying attention, environmentalist and the mainstream narrative has been cracking down on beef as a critically harmful contributor to climate change. Entire books have been written on the environmental impacts of beef, both positive and negative, with the mainstream narrative remaining largely inconclusive. The collective confusion around beef deserves an article to itself. Since cattle and livestock production plays a component of a larger system that stands to offer huge promises in reducing carbon and greenhouse gas emissions, it seems foolish to blindly dismiss the positive effects cattle and livestock can have on the carbon sequestration process.

Lastly, in a study conducted by Will Harris of White Oak Pastures, a third-party named Quantis concluded that the carbon footprint of Will’s farm in Georgia had a net negative effect, which ranked higher than conventional beef, Beyond Burger, and soybean production in the US. When George Washington talked about his vision for restoring the old soil in the original farmland, he grasped a vision for a regenerative future.

Written by: @clemenza